By, Jennifer Calihan and Nina Teicholz

Key points:

Recommended protein amount in the guidelines has decreased over time;

Plant-based proteins have steadily crept into the “protein group”;

The expert committee is currently modeling diets with even less protein and dairy. Reductions will most likely be in the dairy food group. A vegan “dietary pattern” is also being considered.

The expert committee reviewing the science for the next U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans is considering major changes to the protein food groups. An analysis of the last two public meetings of the expert committee, in September 2023 and January 2024, indicate a strong possibility that these groups with meat and dairy may be reduced or diluted by plant proteins, continuing a steady erosion of these categories over the past 20 years.

The expert Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) will inform the next iteration of the guidelines (DGA), due out next year. For this process, which occurs once every five years, the committee is taking a hard look at the protein and dairy food groups while considering questions such as whether these groups should be combined into one and whether recommendations for both food groups should shift towards more plant-based proteins. The committee’s staff, who are employees of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), is modeling different versions of the guidelines to assess nutritional adequacy with ever-smaller amounts of dairy and protein foods, even down to zero. The expert committee may then decide to recommend reduced protein or dairy servings for the next guidelines.

What the ‘Public’ is Saying

Public comments delivered by video to the USDA, which co-issues the guidelines with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), reflect broad support for a shift towards plant-based proteins.[1]

Some commenters, such as Lianna Levine Reisner, co-founder and president of Plant Powered Metro New York, and David Katz, past president of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine and director of a plant-based advocacy group, argue that plant-sourced protein is more healthful than protein from animals. This belief is founded partly on the opinions of experts such as Frank Hu, head of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who provided testimony for a recent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report on protein sources.[2]

A contrary opinion was offered by Peter Ballerstedt, PhD, a forage agronomist who explained that the bioavailability of amino acids in protein is a crucial matter.[3] Citing a 2021 randomized controlled trial in The Journal of Nutrition, he noted that animal sources provide proteins that humans can absorb more easily than do plants.[4]

Some members of the public mentioned climate change as a reason to move away from animal proteins, even though the official mandate of the DGA is to prevent chronic, diet-related diseases in humans and does not include climate change. At a 2015 Congressional hearing, the USDA-HHS Secretaries Tom Vilsack and Sylvia Burwell specifically rejected incorporating environmental concerns into the guidelines. [5]

Many oral comments, from organizations as diverse as the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma to the Coalition for Healthy School Food, mentioned frustration with dairy recommendations for people who are lactose intolerant. Countering these remarks were several dairy farmers including the Olympian track athlete Elle St. Pierre who highlighted the lack of nutritional equivalency of most plant-based milks, compared to real milk, as the reason why the guidelines should not allow these products to be substituted for real dairy.

The International Food Information Council, a food industry group, and Weight Watchers both said that “equity” was a reason for the guidelines to provide more culturally appropriate options for the nation’s diverse population.

Ultimately, the DGA is obligated by its authorizing statute to prioritize the science of nutrition and human health in the guidelines. Before the expert committee issues its recommendations, expected this summer, the group needs to answer the question: ‘Might higher or lower dietary protein levels move our population towards better health?’

History of Eroding Protein Standards

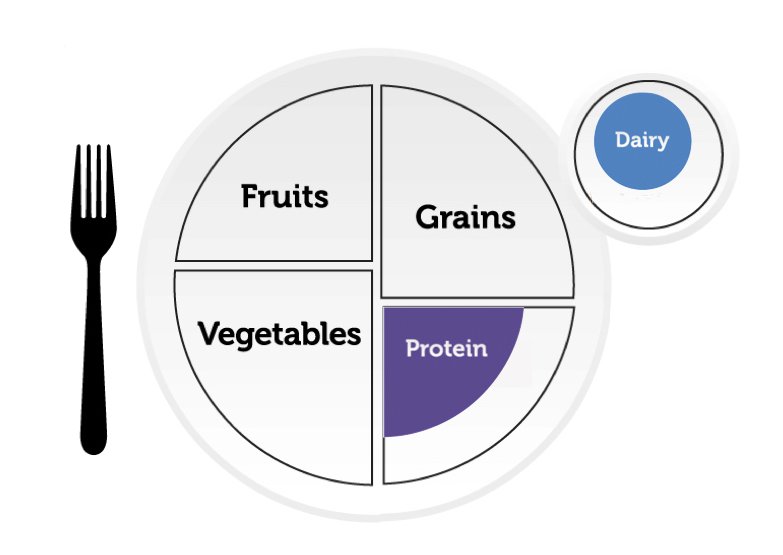

In 1980, the first guidelines began as a 20-page pamphlet that advised Americans to eat a variety of foods while cutting back on saturated fat, total fat, cholesterol, sugar, and sodium. By 1985, the guidelines had settled on the five food groups seen in every edition since: fruit, vegetables, grains, dairy, and protein foods (other than dairy), of which Americans were advised to eat “a variety… in adequate amounts.”

Today’s 150-page guidelines are far more specific. They include three “healthy dietary patterns”: U.S.-Style (omnivorous), Vegetarian, and Mediterranean-Style (which reduces dairy in favor of extra seafood).

In all these patterns, the USDA-HHS have eroded the protein group in recent years, in three ways:

by allowing plant-based proteins to replace animal-sourced proteins;

by shrinking the serving-sizes for all proteins;

by shrinking the serving sizes and serving numbers for plant-based proteins even more.

More Plant-Based Protein Foods

Over the 40-plus years since the guidelines were first issued, they’ve shifted towards plant-based proteins. The protein group started with meat, poultry, fish, eggs, dried beans and peas. Nuts were added in 1990, seeds and soy products in 2010, and lentils in 2020.

Including more plant-based proteins reduces protein quality, since plant-based proteins are often incomplete, lacking in some of the nine essential amino acids that humans need to consume to generate proteins for the body’s growth, maintenance, and repair.[6] In addition, proteins from plants are less bioavailable (meaning, less easily absorbed) than those from animal sources.[7]

| PDCAAS Score |

DIAAS Score[8] |

|

|---|---|---|

| Animal Protein |

1.00 | ≥100 |

| Soybeans | 1.00 | 86 |

| Kidney Beans |

0.65 | 88 |

| Peas | 0.60 | 68 |

| Tofu | 0.56 | 64 |

| Peanuts | 0.51 | 43 |

Lower bioavailability means that if you choose a plant-based protein source, you must eat a higher amount of protein to absorb the same quantity of protein as you would from an animal-protein source.

How much more? Plant sources vary in protein quality, so there’s no single conversion factor. However, experts suggest that people may need to eat 20-50% more grams of plant-based protein to get the same essential amino acids (especially leucine) needed to generate the muscle-repairing response that people get from animal protein.[10]

Shrinking Protein Serving Sizes

In 1990, the DGA for the first time recommended a specific amount of animal protein that American adults should try to consume: 6 ounces per day. Over the years, this amount remained relatively consistent until 2005, when the guidelines expanded to provide specific serving sizes at different calorie levels. The 6-ounce standard was cut to 5.5 ounce-equivalents for a 2,000-calorie-per-day diet (considered the standard amount of calories needed by an American woman). Recommendations have remained at this level in the most common, “U.S.-Style” dietary pattern.

For Plant Proteins, Serving Sizes Get Even Smaller

In the 2000 DGA and earlier, Americans were advised to target about the same amount (by weight) of protein, whether from plant or animal sources. For example, people could substitute two tablespoons of peanut butter, which contains about 7.7 grams of protein, for one ounce of meat or seafood, with a similar amount of protein.

Shockingly, the guidelines in 2005 cut in half the amount of plant protein that was considered equivalent to animal proteins. So, whereas previously two tablespoons of peanut butter were the equivalent of one ounce of meat, now only one tablespoon of peanut butter was deemed sufficient. All of the ounce-equivalent serving sizes for plant-based sources of protein were likewise cut in half that year: ½ cup of cooked beans became ¼ cup; ⅓ cup of nuts became half that.[11]

The USDA explains that it adjusted the sizes to make the caloric content of the plant protein equal to the calories from animal proteins (Plant-based proteins require many more calories to get the same amount of protein, due to their additional carbohydrate content). The USDA’s logic was that since American diets typically have plenty of both protein and calories, the greater imperative in the midst of an obesity epidemic was to restrict calories. (Unfortunately, this reasoning ignores the science showing that protein provides satiety and helps with weight loss.[12] )

The change meant that anyone choosing plant-based options in, say, the National School Lunch Program (based on the DGA), got much less protein.

In 2015, the DGA also further reduced the protein content of the USDA “vegetarian pattern,” lowering the daily protein goal from 5.5 to 3.5 oz-equivalents. Ultimately, a vegetarian following the guidelines would consume only 80 grams of protein, far lower than the government’s other dietary patterns.

| Fruit |

Vegetables |

Grains | Protein Foods |

Dairy | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.-Style |

2 | 9 | 17 | 38 | 27 | 93 |

| Mediterranean | 3 | 9 | 17 | 44 | 18 | 91 |

| Vegetarian |

2 | 9 | 19 | 23 | 27 | 80 |

An even more protein-restricted vegan “dietary pattern” is being considered for the next guidelines.

Do Animal Proteins Cause Disease?

Although the USDA-HHS have steadily shifted towards plant-based proteins, the agencies’ own reviews consider the evidence against animal protein to be weak at best.

In 2010, the USDA’s Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) staff undertook a thorough review on the relationship between various protein sources and health issues such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. In a 476-page summary of its findings, the NESR had very little to report. With the exception of some “moderate-quality” evidence to show that dairy consumption is healthful, the results showed either no relationship or a “limited, inconsistent” relationship between any kind of protein and chronic disease.

On what evidence, then, does the health halo supporting plant-based protein rest? Numerous large observational studies suggest potential concerns about a high consumption of animal protein. Some of these studies reveal weak associations between diets high in animal protein and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.[14] Others suggest that diets high in soy protein are associated with less heart disease.[15] When it comes to overall mortality, plant protein is associated with lower rates of death.[16]

These associations are too small to be considered meaningful, however, and these data — from observational studies — are considered a low-quality source of evidence. Further, all these studies are likely to suffer from a healthy-user bias as a confounder.[17] Most importantly, data from randomized controlled trials, which could demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship, are lacking. The USDA itself could not find any strong evidence to show that plant proteins are good for health or that animal proteins are detrimental.

The shift towards more plant-based protein over the years can therefore not be explained by data demonstrating that such a move improves health. One can only speculate whether powerful food lobbies for the grain and soy industries, as well as environmental and animal-rights activists, might be driving these changes.

Do the Guidelines Meet Our Protein Needs for Health?

Another debated topic among experts is how much protein is needed for basic sustenance versus optimal health.

Perhaps the most commonly cited protein standards are the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA), set by the National Institutes of Health, which recommends that women consume at least 46 grams of protein daily and men, 56 grams. These RDAs are daily minimums to avoid deficiency of nitrogen balance, not amounts that are considered optimal for human health.

Many experts believe that ideal protein levels for adults are roughly double the RDA, or about 100 grams of protein for the average woman and 120 grams for the average man.[18] If we take bioavailability into account, these amounts should be even higher for vegetarians and vegans whose plant-based protein selections are not as easily absorbed by the body.

| Standard | Women (2,000 calories/day) |

Men (2,600 calories/day) |

|---|---|---|

| AMDR [19] | 50-175 | 65-228 |

| RDA | 46 | 56 |

| DGA: “US-Style” | 93 | 112 |

| "Mediterranean" | 91 | 115 |

| "Vegetarian" | 80 | 99 |

| Average adult intake [20] | 69 | 94 |

| Ideal (mostly animal protein) | ~100 | ~120 |

| Ideal (mostly plant protein) | ~125 | ~150 |

The key observation here is that all USDA dietary patterns meet both the RDA and Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) standards for protein. But all patterns fall below the protein levels that many experts consider ideal for building and maintaining lean body mass. Neither adult men nor women currently meet ideal intakes for protein in the U.S.

For children, dietary protein is recognized as a key raw material for growth, development, and to prevent stunting. But the protein RDAs for children in different age groups are bare minimums, not the ideal needed to support optimal growth.[21]

On the other end of the age spectrum, older adults also need greater amounts of protein to prevent sarcopenia and osteoporosis, according to a large body of research. Data show that the bodies of older adults are less efficient in responding to protein and need to eat more to stimulate anabolic processes like muscle building and tissue repair.[22] Unfortunately, the current U.S. guidelines adjust protein levels slightly downward for seniors.

Further, protein may be important in preventing type 2 diabetes. Frankie Stentz, a Professor of Medicine, Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at University of Tennessee Health Science Center, has demonstrated in a small trial that diets high in protein can reverse prediabetes.[23] More research in this area is needed.

The Puzzle of Appropriate Dairy Recommendations

The dairy food category has traditionally included just milk, cheese, and yogurt. Starting in 2010, the DGA officially added soy beverages to its top-line summary of the dairy group.[24] Soy milk, when fortified with calcium, comes close to the nutrient profile of cow’s milk, although it is poor in some essential amino acids, especially methionine, leucine, and isoleucine.[25]

One of the reasons for adding soy milk is that some 36% of Americans, according to NIH estimates, have trouble digesting the lactose in milk, experiencing gastric distress. Black, Hispanic and Asian Americans are more likely to experience these issues than those of European ancestry.

Even in 1995, long before soy milk was officially added to the dairy food group, the guidelines acknowledged that some Americans prefer to avoid dairy products and directed these Americans to other food sources rich in calcium (without mentioning the need to keep an eye on protein, however).[26]

Current U.S. consumption of dairy products falls well below the three servings a day that the guidelines recommend. The survey “What We Eat In America,” conducted by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), tells us that women, age 31-59, consume, on average, just over one serving of dairy each day. Men consume, on average, just under two servings.[27] The missing servings of dairy mean that people are not meeting even minimum protein goals — as much as 18 grams less per day for the average woman. Dairy is also a vital source of calcium and vitamins A and D, which further compromises nutrition for those who under-consume these foods.

Despite the growing selection of alternative “milks” in our supermarket dairy cases, the 2020 guidelines specifically counsel Americans to avoid substituting dairy with any plant-based milks except fortified soy milk.[28] Thus, consuming almond, cashew, oat, or hemp “milk” is fine, but the guidelines don’t count those as a serving of dairy.

Disallowing these plant “milks” is arguably appropriate. Regardless of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s laissez faire attitude about the permitted use of the word “milk” for what are essentially plant juices, the protein levels in these products are far too low to treat them as nutritional equivalents to cow milk.[29] However, in 2025, due to a new “health equity focus” by the DGAC,[30] we may see more of these plant-based milk substitutions in the guidelines.

Looking Ahead to DGA 2025

Protein is foundational to human health; to a large extent, it is the macronutrient we’re made of. For this reason, protein has anchored our meals for decades. But protein’s share of our plates has shrunk, both through official guidance and its declining popularity at large. Further, our collective shift toward emphasizing more plant-based foods has lowered the quality and quantity of protein in our diets. It is time to pause and question whether these changes are endangering health in the US, especially among children and the elderly. Still, with plant-based advocates dominating the public comments, plant-based industries and interests lobbying the USDA, and plant-based proponents on the expert committee itself, we may see further reductions of this important macronutrient in the 2025 Dietary Guidelines.

[1] Click through for a transcript of the public comments made September 12, 2023.

[2] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2023. Alternative Protein Sources: Balancing Food Innovation, Sustainability, Nutrition, and Health: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26923.

[3] Public comments delivered 9/12/2023. Page 22.

[4] Park S, et al. Metabolic Evaluation of the Dietary Guidelines' Ounce Equivalents of Protein Food Sources in Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Nutr. 2021 May 11;151(5):1190-1196. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa401.

[5] In 2015 USDA blog post, Secretaries Vilsack and Burwell specifically addressed the issue of whether or not the DGA would consider a food source's sustainability, explicitly rejecting environmental considerations in favor of keeping the scope of the guidelines focused on matters of nutrition and health. This did not change in 2020.

[6] The exception is soy protein, which does contain all nine essential amino acids, albeit in less-than-ideal quantities.

[7] Berrazaga I, et al. The Role of the Anabolic Properties of Plant- versus Animal-Based Protein Sources in Supporting Muscle Mass Maintenance: A Critical Review. Nutrients. 2019 Aug 7;11(8):1825. doi: 10.3390/nu11081825; Pinckaers PJ, et al. Higher Muscle Protein Synthesis Rates Following Ingestion of an Omnivorous Meal Compared with an Isocaloric and Isonitrogenous Vegan Meal in Healthy, Older Adults. J Nutr. 2023 Nov 15:S0022-3166(23)72723-5. doi: 10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.11.004.

[8] van den Berg LA, et al. Protein quality of soy and the effect of processing: A quantitative review. Front Nutr. 2022 Sep 27;9:1004754. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1004754.

Han F, et al. Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Scores (DIAAS) of Six Cooked Chinese Pulses. Nutrients. 2020 Dec 15;12(12):3831. doi: 10.3390/nu12123831.

Rutherfurd SM, et al. Protein digestibility-corrected amino acid scores and digestible indispensable amino acid scores differentially describe protein quality in growing male rats. J Nutr. 2015 Feb;145(2):372-9. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.195438.

[9] Both the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) and the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) assess protein digestibility. DIAAS is newer, and recognizes each essential amino acid as an individual nutrient. DIAAS measures ileal digestibility rather than total tract digestibility measured by PDCAAS.

Bailey HM, Stein HH. Can the digestible indispensable amino acid score methodology decrease protein malnutrition. Anim Front. 2019 Sep 28;9(4):18-23. doi: 10.1093/af/vfz038.

[10] Berrazaga I, et al. The Role of the Anabolic Properties of Plant- versus Animal-Based Protein Sources in Supporting Muscle Mass Maintenance: A Critical Review. Nutrients. 2019 Aug 7;11(8):1825. doi: 10.3390/nu11081825.

[11] A serving of soy is the only plant-based substitution that now contains more protein, about 11.8 grams per ounce-equivalent, than animal protein sources, which average about 7.0 grams per ounce-equivalent. Nuts and seeds average just 3 grams per ounce-equivalent, and beans and peas contain around 4 grams per ounce-equivalent.

[12] Paddon-Jones D, et al. Protein, weight management, and satiety. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008 May;87(5):1558S-1561S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1558S.

[13] Protein per servings of each food group sourced from “Nutrient Profiles for Food Groups and Subgroups in the 2020 USDA Food Patterns” data in the Food Pattern Modeling report of 2020 DGAC, page 43.

[14] Malik VS, Li Y, Tobias DK, Pan A, Hu FB. Dietary Protein Intake and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women. Am J Epidemiol. 2016 Apr 15;183(8):715-28. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv268.

[15] Ma L, et al. Isoflavone Intake and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in US Men and Women: Results From 3 Prospective Cohort Studies. Circulation. 2020 Apr 7;141(14):1127-1137. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041306.

[16] Song M, Fung TT, Hu FB, et al. Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine 2016;176(10):1453–1463. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4182

[17] Healthy-user bias refers to a common source of confounding in observational studies. When these studies find, say, an association between a diet high in vegetables and lower cancer rates, this finding is inevitably confounded by the fact that people who make an effort to eat more vegetables are also the type of people who generally follow expert advice. (For example, they also tend to exercise more, refrain from smoking or excessive alcohol consumption, avoid soda, etc.) Any one of these factors that is associated with better health could be responsible for the reduced cancer risk. Despite advancements in statistical analysis, researchers cannot adjust for all the ways that healthy people are different from unhealthy people. Many of these factors, such as meaningful personal relationships, are not even measured.

[18] Layman DK. Dietary Guidelines should reflect new understandings about adult protein needs. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2009 Mar 13;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-6-12.

Phillips SM, Chevalier S, Leidy HJ. Protein "requirements" beyond the RDA: implications for optimizing health. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016 May;41(5):565-72. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0550.

Weiler M, Hertzler SR, Dvoretskiy S. Is It Time to Reconsider the U.S. Recommendations for Dietary Protein and Amino Acid Intake? Nutrients. 2023 Feb 6;15(4):838. doi: 10.3390/nu15040838.

Morton RW, et al. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Mar;52(6):376-384. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097608.

[19] The ADMR (Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range) for protein is 10-35% of total calories. This standard is designated by the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM).

[20] What We Eat in America (WWEIA), National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2017-2020.

[21] Hudson JL, et al. E. Dietary Protein Requirements in Children: Methods for Consideration. Nutrients. 2021 May 5;13(5):1554. doi: 10.3390/nu13051554.

[22] Bauer J, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013 Aug;14(8):542-59. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.021.

Baum JI, et al. Protein Consumption and the Elderly: What Is the Optimal Level of Intake? Nutrients. 2016 Jun 8;8(6):359. doi: 10.3390/nu8060359.

[23] Stentz FB, Brewer A, Wan J, Garber C, Daniels B, Sands C, Kitabchi AE. Remission of pre-diabetes to normal glucose tolerance in obese adults with high protein versus high carbohydrate diet: randomized control trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2016 Oct 26;4(1):e000258. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000258.

[24] Fortified soy milk was first mentioned as an acceptable substitute for dairy in the detailed text of the guidelines in 2000, but the summary information that most Americans see does not list it until 2010.

[25] Walther B, et al. Comparison of nutritional composition between plant-based drinks and cow's milk. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022 Oct 28;9:988707. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.988707. Supplementary Materials, Table 3.

[26] Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 1995-2000, page 32.

[27] Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, page 99.

[28] Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, page 33.

[29] The FDA issued draft guidance in February 2023 that suggests manufacturers of plant-based beverages may use the word “milk,” but suggests that product labels include a statement that describes how products are nutritionally different than milk, such as: “Contains lower amounts of protein, potassium, and magnesium than milk.” In the draft guidance, this statement is voluntary.

[30] By design, the Health Equity Working Group, chaired by Sameera Talegawkar, PhD, has members who sit on each of the four DGAC subcommittees.