Reversing Diabetes in Alabama

By Jennifer Calihan

Board Member, Nutrition Coalition

Sometimes, a well-timed email can make a real difference. For Michael Collins, age 53, that life-changing message arrived from his employer’s wellness initiative in October 2020. It was the Monday after his doctor had told him that he was “in trouble” and needed to get his weight and diabetes under control.

Michael, a resident of Boaz, Alabama, and a mental health advocate for his state government, explained the extent of his health crisis:

“The doctor told me that he couldn’t promise me [I would live] two weeks or six months. I mean, I was having heart palpitations… my heart was messing up. I couldn’t breathe, I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t sleep. I was in bad shape.”

Michael Collins in 2018.

The fateful email included an invitation to apply to a diabetes reversal program offered by a company called Virta Health. Michael filled out the forms and enrolled, initiating a remarkable health journey. He was one of more than 1,100 government employees who signed up (a mix from both state and local governments).

Over the coming months, he would lose 190 pounds and eliminate five diabetes medications. His hemoglobin A1c, a measure of average blood sugar, would fall from 8.1%, well above the 6.5% level that indicates a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, down to 5.0%, a healthy result in the normal range. Michael had effectively reversed his type 2 diabetes.

Michael Collins in August, 2023, after losing 190 pounds with Virta Health

The idea of reversing a type 2 diabetes diagnosis is quite new.[1] Since the 1900s, when doctors started seeing the disease enough to discuss it in the medical literature, they viewed the disease as irreversible, progressive, and incurable. That’s because standard diabetes care, which advises patients to eat a diet rich in fruit, vegetables, and whole grains, will often slow the progression of their disease yet rarely stop or reverse it. Over time, most patients need more medications or higher doses of existing medications, and they begin to experience the damaging effects on sensitive tissues that are inevitably caused by consistently high blood sugars.

When managed conventionally, diabetes can lead to serious complications such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, kidney failure, amputations, blindness, and more. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one in four healthcare dollars is spent to care for people living with diabetes, which amounts to almost $900 million a day. On average, a diabetes diagnosis more than doubles a person’s annual medical expenses, costing employers more than $20,000 per patient each year. It’s a debilitating and expensive problem that now affects over 37 million Americans.

But there is hope. A low-carbohydrate approach for type 2 diabetes has been studied extensively over the past ten years such that now, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the American Heart Association (AHA) both acknowledge its effectiveness. The ADA points to low-carb diets as the best for controlling blood sugar, the key issue for reversing the disease.[2] And the AHA touts low-carb diets as best for weight loss when calorie counting fails and notes low-carb diets improve both triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol, two important risk factors for heart disease.[3]

With the right lifestyle changes and support, the evidence suggests that more people like Michael can use a low-carb diet to reverse their diabetes and reclaim their health.

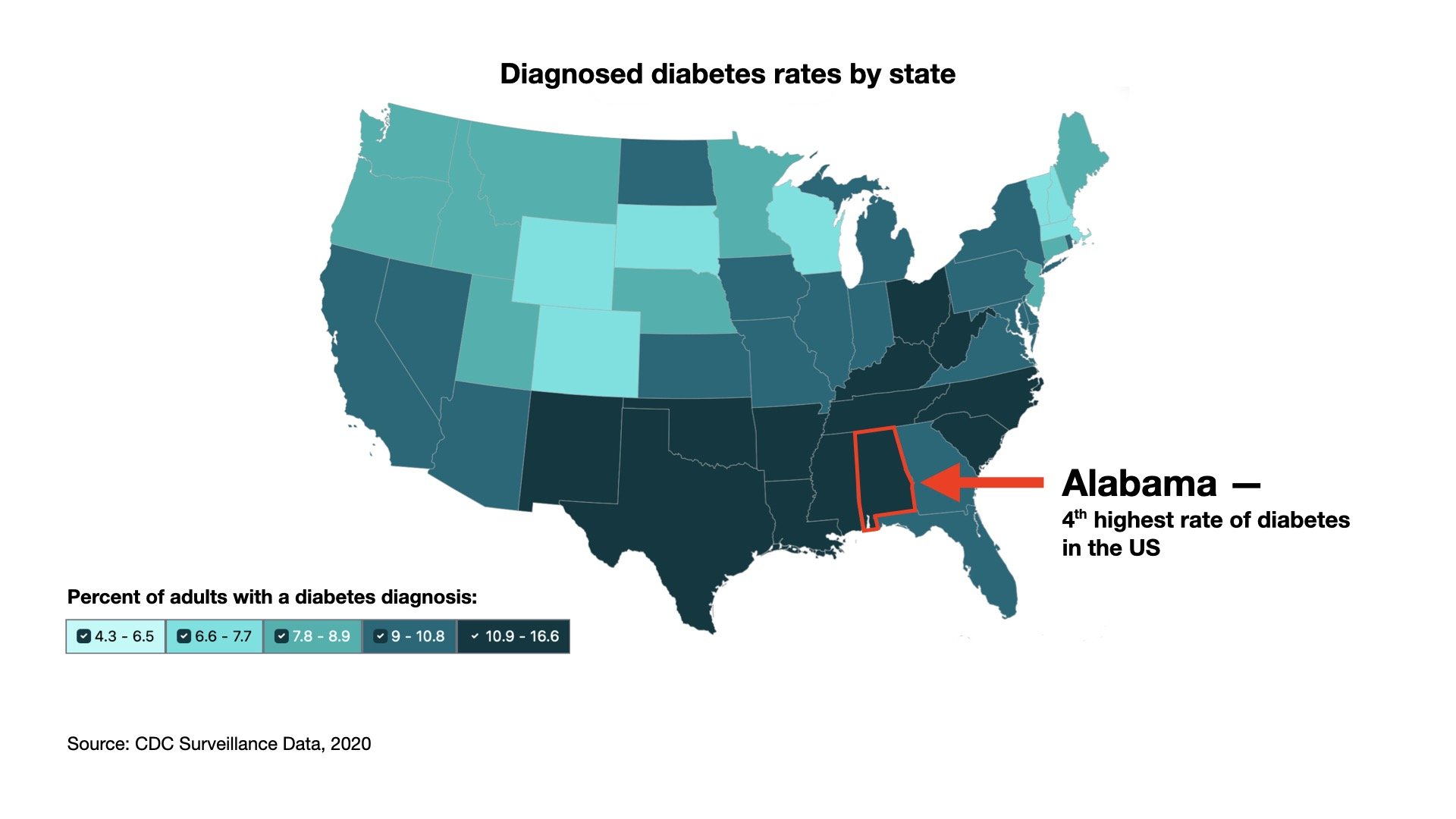

Alabama has the 4th-highest diabetes rate in the nation

Almost 13% of adults in Alabama have been diagnosed with diabetes. Among state government employees like Michael, those numbers rise to 19%, according to the Alabama State Employee Insurance Board (SEIB), an insurance company. Diabetes drives up insurer costs and creates other problems, such as lower productivity and absenteeism due to illness. In 2020, SEIB searched for solutions and discovered Virta Health.

Virta aims to give its patients a diabetes reversal clinic at their fingertips. Patients receive a starter kit with a scale that connects to patients’ smartphones for tracking weight loss, and other supplies: a glucose meter, a ketone meter, test strips, and some supplements. Then, through a phone-based app, Virta providers coach clients to adopt a low-carb diet — personalized to each person’s budget and preferences. Patients enter their blood sugar and ketone levels (both tests that monitor adherence to a low-carb diet) through the app, which Virta doctors monitor, in order to help patients safely reduce or even eliminate medications, like insulin, which are no longer needed — since a low-carb diet will naturally lower blood sugars.

Although many people believe a low-carbohydrate diet is unaffordable, the state and local government employees enrolled with Virta, who come from all walks of life, seem to manage. In fact, neighborhoods with the lowest income levels were over-represented in the Virta program: nearly half lived in areas that rank in the bottom 40% of U.S. neighborhoods, according to an established measure called Area Deprivation Index (ADI).[4] These populations are average or even underserved.

Impressive real-world results

So, how did these everyday Alabamans do?

Remarkably well.

According to Virta, after one year, hemoglobin A1c was down a full percentage point, falling to an average of 6.6% among the participants who stayed in the program. Over half of the participants achieved an A1c below 6.5%, meaning they no longer had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. With usual care, one would expect to see A1c increase over time, so this decline is impressive, if not a bit miraculous.

Further, Virta participants reduced their A1c while reducing or eliminating medications typically used to lower blood sugar. Virta docs deprescribed 46% of diabetes-specific prescriptions (excluding metformin), and over half of the participants were able to discontinue insulin completely. This was true regardless of socioeconomic (SES) status. In fact, people living in underserved areas did even slightly better than those in higher SES areas.

By contrast, with usual care, one would expect the number of patients requiring prescriptions (other than metformin) to increase as much as 7% in a year.[5]

Weight loss was also impressive. Patients who remained in the program for an entire year lost an average of 18 pounds, or 7.7% of body weight. A few, like Michael, experienced dramatic weight loss, but about a third lost more than 10% of their body weight. Again, those in lower-SES status neighborhoods did slightly better. Some 62% of people in underserved communities lost at least 5% of their body weight versus 56% in the higher-SES neighborhoods.

Teaching people how a low-carbohydrate diet can be affordable was part of the challenge. Michael reflects that his food budget didn’t change much when he switched to the diet. Although carb-heavy junk food like potato chips has a reputation for being cheap, it still isn’t free. So when patients eliminated the cookies, crackers, chips, and cereal, they could find room in their budgets for inexpensive low-carb foods like eggs and ground beef. And Virta helped direct patients to convenient on-plan options like fast food burgers minus the bun and fries.

What Michael did notice was that he started to save money on insurance co-pays as soon as his diabetes medications were reduced. Michael estimates he now saves about $200 a month on medications he no longer takes. He touts these savings to his colleagues, many of whom he knows are heavily burdened by medication costs.

Michael said he reaches out to colleagues and friends when he can:

“There’s a lot of people like me still out there right now and I know what they are living because I lived it… When I see someone as obese as I was, I try to talk to them and say, ‘Hey, you don’t have to live like this anymore. You can change it, by just what you are eating…’ It is a sad life being that large of a person… I could barely do my job, you know, to support my family… Those people at Virta, they saved my life.”

Jessica O’Donnell, a benefit services director for the local government department running this program, commented in an interview on the cost savings from an employer’s perspective:

“These members have less emergency room utilization, and they have shorter hospital stays… So it is not just prescription drug costs that have been lowered, but our medical costs have been lowered as well.”

More specifically, O’Donnell stated that Virta participants have 25% fewer emergency room visits, and if admitted to the hospital, their stays are almost 80% shorter. Overall, medical and pharmacy spending for employees not on Virta was 125% higher than similar employees enrolled in the program.

O’Donnell says she was surprised by how profoundly the Virta program transformed the lives of its patients:

“We’ve had [participants] come and give their testimony that they were at rock bottom, that they never left their house because they were embarrassed and in such bad health, and that they were so overweight that they couldn’t get in their cars. Their life has been changed so significantly that now they are playing with their grandkids and able to participate in life again. Just to hear the members’ testimony… it’ll bring tears to your eyes.”

Is conventional thinking on diet suppressing enrollment?

With such broad success and glowing reviews, one might expect that all of Alabama’s government employees with type 2 diabetes would have signed up to participate in Virta. The state makes it easy and free, and even encourages annual wellness screenings to identify those who might benefit from the program. The state also sends emails encouraging people with diabetes to apply, like the one Michael received.

However, participation rates remain quite low. The insurer SEIB reported in an interview that only about 20% of qualifying employees have signed up, and another insurer told us that number was just 8%. These low participation rates beg the question of why more people don’t enroll. Why not at least try to reverse a disease that requires costly medications and will inevitably shorten one’s life? Does the promise of diabetes reversal, after so many years of considering the disease a life-long sentence, seem inconceivable?

One possibility is that widespread suspicion of the low-carb diet contributes to the hesitation. More people might participate if more doctors, dietitians, and public health institutions encouraged this approach.

Many clinical trials now exist to show that the reversal of type 2 diabetes is possible — and safe. Virta funded one of those trials, conducted at Indiana University on some 349 subjects, with the results documented extensively in peer-reviewed publications.[6] These papers report not just on key metrics, like A1c reduction and medication elimination but also on other health measures, such as blood pressure, blood lipids, liver and kidney health, as well as markers of inflammation. Virtually every health metric is seen to improve on a low-carbohydrate diet — with the exception of the “bad” LDL-cholesterol. Yet the rise in this type of cholesterol can be transient. Meanwhile, 22 of 23 other cardiovascular risk factors improve on the diet, making the overall heart-disease profile for these subjects much improved.[7]

Reversing type 2 diabetes through a low-carbohydrate diet is clearly an evidence-based approach. Yet, thus far, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which runs the scientific reviews for the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the nation’s top nutrition policy, has neglected to acknowledge any of the more than 100 clinical trials on this diet. In the scientific reviews currently underway for the next iteration of the guidelines, due out in 2025, the USDA has declined even to examine this scientific literature.

So long as the “gold standard” Dietary Guidelines ignores the existence of low-carbohydrate diets, the public is likely to continue shying away from this nutritional option, and Alabamans may continue to cast a wary eye on Virta, despite the program’s impressive results. This is more than a shame for the many people who have diabetes, not just in Alabama but in all of America, across all walks of life.

[1] Shibib L et. al. Reversal and Remission of T2DM – An Update for Practitioners. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2022;18:417-443 https://doi.org/10.2147/VHRM.S345810

[2] “Reducing overall carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes has demonstrated evidence for improving glycemia and may be applied in a variety of eating patterns that meet individual needs and preferences. For people with type 2 diabetes, low-carbohydrate and very-low-carbohydrate eating patterns in particular have been found to reduce A1C and the need for antihyperglycemic medications.” From the ADA’s Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023

[3] “Very low–carbohydrate versus moderate carbohydrate diets yield a greater decrease in A1c, more weight loss and use of fewer diabetes medications in individuals with diabetes. For those who are unable to adhere to a calorie-restricted diet, a low-carbohydrate diet reduces A1c and triglycerides. Very low–carbohydrate diets were effective in reducing A1c over shorter time periods (<6 months) with less differences in interventions ≥12 months.” From the AHA’s Comprehensive Management of Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association

[4] The CDC explains Area Deprivation Index as a tool to assess local area deprivation that may be associated with health outcomes in this research brief: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2016/16_0221.htm

[5] Hallberg et al. Effectiveness and Safety of a Novel Care Model for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes at 1 Year: An Open-Label, Non-Randomized, Controlled Study. Diabetes Therapy 9, 583–612 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-018-0373-9

[6] Hallberg et al. Effectiveness and Safety of a Novel Care Model for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes at 1 Year: An Open-Label, Non-Randomized, Controlled Study. Diabetes Therapy 9, 583–612 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-018-0373-9

[7] Bhanpuri, N.H. et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factor responses to a type 2 diabetes care model including nutritional ketosis induced by sustained carbohydrate restriction at 1 year: an open label, non-randomized, controlled study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 17, 56 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0698-8